(This is an updated, slightly expanded version of a 2013 post that originally appeared on the Fred Rogers Center Blog.)

Is screen media technology more like a germ or a medicine?

If technology devices are like germs, then we grudgingly accept them as part of children’s worlds, but we work to limit contact as much as possible. If they are akin to a medication, then we should be able to determine an optimal dose while also understanding that using too much or none are both dangerous.

In essence, these are the choices offered by the public health approach that has guided the use of technology in early childhood education for decades. But in the real world – a world where digital media are integral to culture and daily life — those two options are too limiting.

In states across the U.S., medical sources underpin nearly all child care licensing rules governing the use of technology with young children. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Caring for Our Children (CFOC), and the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS) are all written from a medical perspective.

Medical language permeates the discourse. Advocates pathologize descriptions of their concerns with phrases like “play deficit disorder.” Researchers refer to education activities as “interventions.” Even the first principle in the Fred Rogers Center’s “Framework for Quality in Digital Media for Young Children” (2012) takes a “do no harm” approach, underscoring the need for digital media to “safeguard the health, well-being, and overall development of young children.”

In this medical model, the goal is to keep children safe from media harms and the resulting teaching strategies are borrowed from public health educators. At first glance, that seems to make a lot of sense, especially given that public health strategies can be phenomenally successful. Consider, for example, the CDC’s campaign against smoking. Once portrayed as glamourous and common, cigarette smoking in the U.S. today is restricted in public spaces and only about 15% of American adults smoke.

HOWEVER…

Public health education methods only work well when the information that needs to be conveyed and the desired action is simple and concrete. Hence the success of the anti-smoking campaign: cigarette smoking is likely to kill you, so don’t smoke. There’s no need for nuance or a wide array of personalized alternatives.

But when we’re talking about a digital world where screens are now necessary for many daily routines and social media serve as an online digital commons for political discourse and cultural expression, the simplicity that’s necessary for public health messaging doesn’t exist. This forces public health models into a reductionist approach that doesn’t serve children very well.

The process looks something like this: When applied to digital media, the public health goal is expressed as the question, “How do we keep children safe?” When you “backwards map” to design curriculum based on that goal, you invariably end up with limits on screen time (and often not much else). In fact, screen time limits dominate the recommendations proffered by AAP and CFOC. (To their credit, the AAP also recommends media literacy education for children older than five, a recommendation that is too often ignored.)

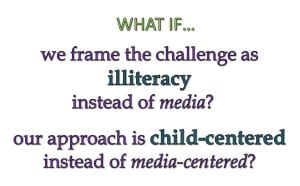

The thing is, children don’t acquire skills or knowledge from an approach that is basically a game of keep-away. Of course, safety is a prerequisite for learning, so educators won’t be abandoning the medical paradigm anytime soon, nor should they. But it’s an odd starting point for educational design. Have you ever heard someone say that they nurture emergent literacy or number sense in order to keep children safe? So what happens if we change the paradigm? What if the launch pad for technology integration is instead the question, “How do we help children become literate in a digital world?” Now, rather than focusing on counting minutes of screen time, we get a rich array of activities and interactions that help children develop the “habits of inquiry and skills of expression necessary for people to be critical thinkers, thoughtful and effective communicators, and informed and responsible members of society,” as the National Association for Media Literacy Education puts it in its Core Principles.

So what happens if we change the paradigm? What if the launch pad for technology integration is instead the question, “How do we help children become literate in a digital world?” Now, rather than focusing on counting minutes of screen time, we get a rich array of activities and interactions that help children develop the “habits of inquiry and skills of expression necessary for people to be critical thinkers, thoughtful and effective communicators, and informed and responsible members of society,” as the National Association for Media Literacy Education puts it in its Core Principles.

What happens is something like Vivian Vasquez and Carol Felderman’s tomato plant project. In that project, children grew tomato plants and also:

- analyzed a TV ad targeted at gardeners,

- conducted a scientific experiment to test the claims of the ad,

- discussed gender stereotyping in the ad,

- did Internet research, and

- used Word Clouds to compare websites about growing tomatoes.

These activities seamlessly integrated screen-based technologies, using them to do things that would be nearly impossible without digital tools. At the height of the project, children certainly surpassed the ECERS 30-minute per week limit on screen time, though I suspect that even the most strident opponent of technology would be hard-pressed to label what happened in this class as anything but excellent practice.

In fact, many researchers now reject the term “screen time” altogether because in a world where so many diverse activities involve screens, the phrase isn’t useful as a meaningful variable. It’s increasingly clear that what children are doing with screens is much more important than how much time they spend using a screen device. Even the AAP now acknowledges that counting minutes is an outdated approach,

“Because children and adolescents can have many different kinds of interactions with technology, rather than setting a guideline for specific time limits on digital media use, we recommend considering the quality of interactions with digital media and not just the quantity, or amount of time.”

Vasquez and Felderman are not alone in ensuring that time spent with media technologies is rich and rewarding. Brian Puerling (Teaching in the Digital Age, 2012), Renee Hobbs and David Cooper Moore (Discovering Media Literacy, 2013), or even my own 2020 ISTE Early Learning PLN webinar or recent book, Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates (NAEYC, 2022), all offer similar examples of technology integration. What distinguishes these examples is that they don’t merely use screen time to introduce or rehearse disconnected skills. None of them involves a child sitting alone using an “education” app on a tablet or watching videos on a phone. Rather, they integrate technology in much the same way that teachers integrate books, crayons, and storytelling – as tools that help us explore the world and share ideas.

When technology is integrated in the ways envisioned by the NAEYC-Fred Rogers Center Joint position statement—with intention, developmentally appropriate goals, and a well-informed understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of technology options—it sparks conversations, curiosity, and creativity. As demonstrated by the tomato project, it also provides ample opportunities to practice reasoning, observation, and communication skills.

When we shift the paradigm from safety to education, we open curriculum design to activities and interactions that provide children with the full benefits of being literate. In a digital world, those benefits cannot be achieved without allowing children to engage with technology. And we can’t help children develop digital and media literacy competencies unless we incorporate technologies in ways that are based in sound pedagogy rather than clock management. To put it another way, we can’t accomplish complex educational goals using only a medical model.

I’m reminded of a conversation with friends who were handing over their son to me for a play date. I was the indulgent auntie who occasionally shared otherwise forbidden snacks, computer games, or videos. They jokingly said that we could do whatever we wanted as long as I handed him back alive. It was the quintessential safety argument.

Ironically, it’s often the expectation we have of babysitters. But early childhood educators are so much more than babysitters. Why, then, when it comes to technology would we still hold early childhood professionals to babysitter standards?

Educators who learn to integrate media technologies effectively enrich children’s lives so much more profoundly than people who are relegated to the role of screen time monitor. You can learn more about media literacy education strategies and find a more detailed discussion of the issues raised here in Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates (NAEYC, 2022). If you found this post valuable, please consider purchasing a copy.

May be reprinted for educational, non-profit use with the credit: From the edublog “TUNE IN Next Time” by Faith Rogow, Ph.D., InsightersEducation.com, 2023

If you liked this post, you might want to also take a look at DIGITAL FAMILIES 2022, CHOOSING MEDIA FOR YOUNG CHILDREN, and MEDIA LITERACY AND OUTDOOR EDUCATION FOR YOUNG CHILDREN.